Institutions as Startups

On Burke, Revolution, and the Architecture of Change Through the Lens of the French Army and Navy

Keynes once quipped, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.” Every “new” idea seems to have some older ancestor hiding behind it.

I think Edmund Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France fits this expression quite well. Written during a time of intense disruption during the French Revolution, his complaints against the revolutionary ideals of Republican France could be easily transposed to modern conversations on disruptions in tech. The vocabulary is different, but the anxieties are the same. The modern vision of “moving fast and breaking things” Burke captures as “All the decent drapery of life is to be rudely torn off.”

At its core, Burke’s argument serves not merely as a historical blip but rather as a blueprint for a timeless discussion on the mode and nature of optimal change: ameliorative, which involves step-by-step iterative improvements as advocated by Burke, or revolutionary, which entails breaking things down to first principles and building better from scratch as demonstrated by the French revolutionaries.

For each Burkean perspective on change, there is a corresponding one from Sieyès; for every engineer who patches a bug, there’s a founder who pitches a vision. And since history gives us plenty of context to see how this debate played out, I think it’s worth examining it as a laboratory for lessons.

I. Enlightenment: British Gradualism and French Rationalism

Before we dive into the history, it’s worth grounding ourselves in some conceptual clarity from these two Enlightenment schools of thought. This will inevitably miss some details on the two incredibly varied corpora of works but aims to keep fidelity to the core ideas.

The English

A STATE WITHOUT THE MEANS OF SOME CHANGE IS WITHOUT THE MEANS OF ITS CONSERVATION. (Burke, 1790)

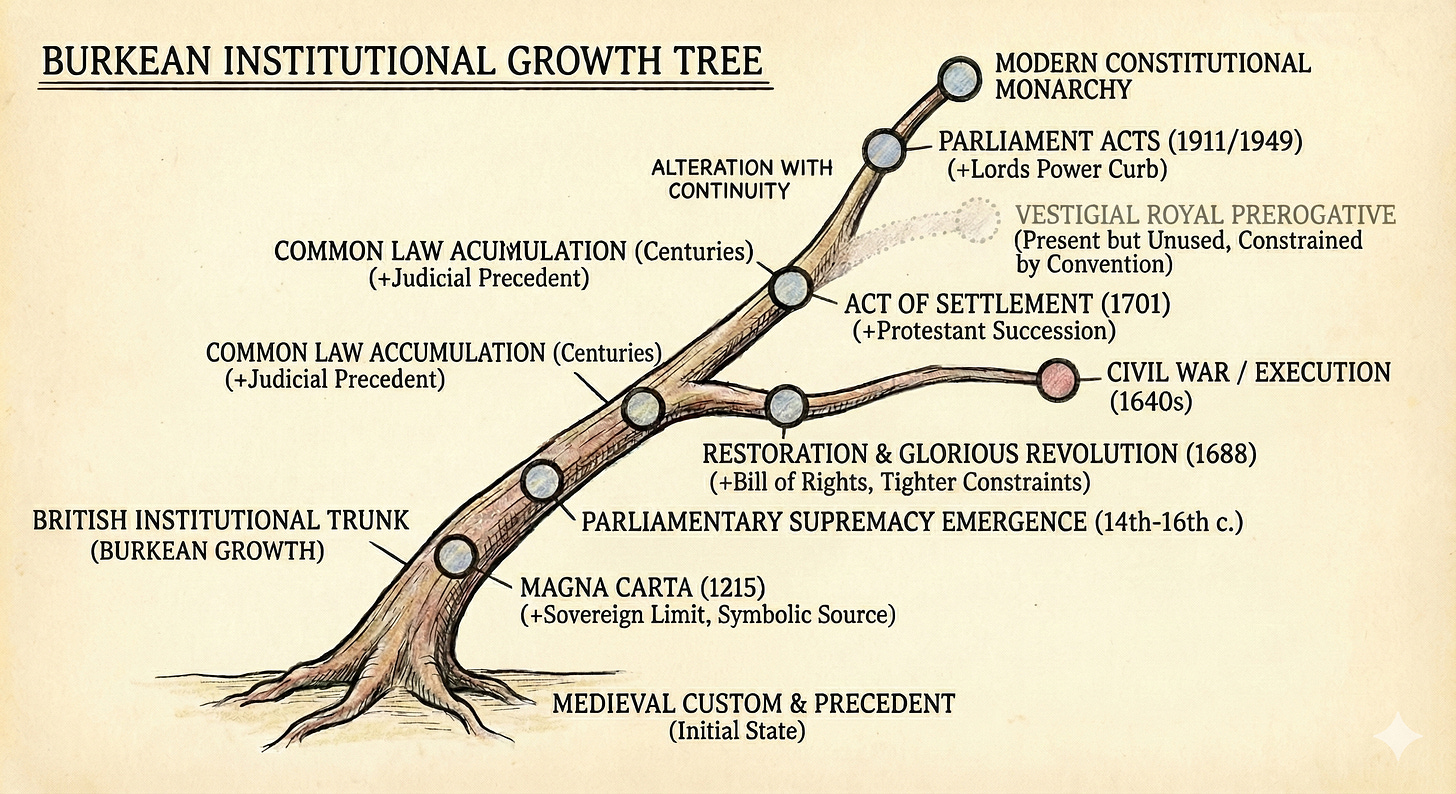

A key component of Burke’s argument is a simple natural premise through analogy: institutions grow the way organisms do. They accumulate the collective experience of the individuals constituting the institution, embed tacit (or implicit) knowledge via customs, expectations, and laws, and ultimately evolve through countless incremental adjustments in lieu of grand redesigns. There’s an emphasis on alteration with continuity; reform should lean on inherited structures and trust in the wisdom of preceding generations rather than discarding them.

You can see this mindset everywhere in British political and legal development. British common law evolves case by case: parliament asserts liberties not through a universal “Declaration of Rights,” but by referencing older charters and precedents. The Magna Carta is hopelessly irrelevant to British citizens today (as its literal clauses mostly concerned the rights of barons), but it’s still referenced as the source of the original limits of sovereign power in Britain, built upon by successive generations.

Curiously, this evolution has resulted in “vestigial” features that demonstrate that these growths in constraints are carried by custom as much as written declarations. Technically, the Crown retains sweeping “prerogative power”; it can dissolve parliament and refuse assent to legislation, yet in practice the powers are constrained by entrenched conventions (the last time Parliament was suspended was under Charles I; it didn’t go too well for him).

Growth thus resembles a branching history tree, built up from an accumulation of past choices and constraints. Instead of cutting off existing branches and starting a new one, the system evolves by extending them. It’s a collection of stacking “git diffs” from commits with an aversion to “git resets --hard.”

The French

If Burke represents the gradualist flavor of Enlightenment thinking towards institutions, the French philosophes approached them as artifacts from reason, able to be evaluated, taken apart, and rebuilt according to clear rationalist first principles. From this perspective, when institutions err in reason, incremental iteration will only reproduce and reinforce their defects without resolving the underlying foundational failures.

If the axioms are wrong, the only remedy is reconstruction, not revision. We can see the persuasiveness of this perspective by viewing those who tried to implement the ideals of philosophes as a product of their time: take the familiar ancien régime Estates of pre-revolutionary France we know from grade school as an example: an omnipresent rigid three-order structure (clergy, nobility, and everyone else) that circumscribed French political life. No amount of patching that foundational system would ever yield equal influence for the middle class, who drove the revolution.

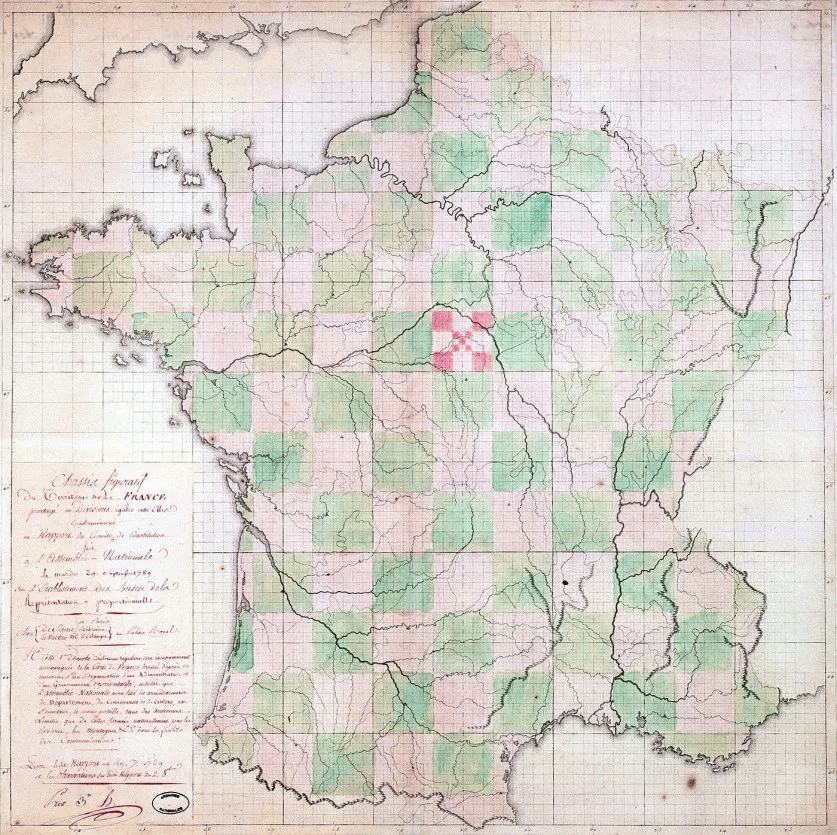

Crucially, sentimental value and historical legitimacy ought to be discarded, with institutional design treated the same way one might toss a previously inaccurate math proof for a correct one. This mindset enshrined coherent argumentation from Type 2 thinking as the master of change, producing both admirable reforms (e.g., legal uniformity and the introduction of the metric system) but also some quirks:

It would be a mistake to straw man these two schools as conservative vs. liberal. Burke supported reform, but he preferred the type that slowly bends institutions into a corrected shape rather than breaking them; and though the French were also radical in their modes of thought, these differences didn’t always mean that their thought culminated into radical policies.

Ultimately, this philosophical divide solidified into institutional habits that were evident in the real world, where competing theories of change faced rigorous testing. Nowhere was this contrast sharper than in the grand enterprise of philosopher-statesmen in the turn of the 19th century in Europe: war.

II. The Army and Navy

I DO NOT SAY, MY LORDS, THAT THE FRENCH WILL NOT COME. I SAY ONLY THEY WILL NOT COME BY SEA. (JERVIS, 1801)

The year is 1801. France has swept through northern Italy and southern Germany, yet Napoleon’s eastern gambit in Egypt has recently collapsed, cut off by the Royal Navy. Jervis, the architect of Britain’s naval reforms, includes an implication that many at the time recognized: France’s revolutionary army is unmatched on the continent, but at sea it struggles to contest Britain’s compounding institutional strength.

Although this asymmetry seems obvious in hindsight, it was far less clear in the decades leading up to the French Revolution. The French Navy—commanded by seasoned professionals such as the Comte de Grasse, d’Orvilliers, and Suffren—was often competitive with, and at moments superior to, the Royal Navy. French naval architects built some of the finest 74-gun ships of the period, with the Royal Navy actually copying their designs. Less than twenty years before Jervis’s remark, during the American War of Independence, France had defeated Britain at the pivotal Battle of the Chesapeake, cutting off British relief and leading to the ultimate surrender at Yorktown. And even in the chaos on the eve of the Revolution, France maintained roughly 80 ships of the line to Britain’s 100, leaving real ambiguity about long-term naval supremacy.

A similar balance existed for the army. Grade-school American narratives tend to overlook just how well a relatively small British force performed in the American War of Independence, operating thousands of miles from home, across vast terrain, and among a largely hostile civilian population. British continental victories in Europe during the Seven Years’ War were just a few episodes of a longer tradition of major success against France on the continent, stretching as far back as Marlborough’s triumph at Blenheim, the first major British-led battle in the heart of Europe and a decisive check against French continental ambitions.1

In other words, both sides recognized an edge, but only an edge—something that could be credibly challenged, not the overwhelming asymmetry we now project backward. The dual hegemonies we now associate with the Napoleonic era, marked by Britain’s decisive naval victory at Trafalgar and France’s crushing land victory at Jena-Auerstedt within one year of each other, had not yet come into view.

I argue that this split, which appears so clean in retrospect, was the result of contrasting outcomes between Burke’s gradual institutional evolution and the efforts of those who sought to implement the philosophe’s ideals through radical institutional reconstruction, a visibility that would only emerge after the Revolution.

The Army

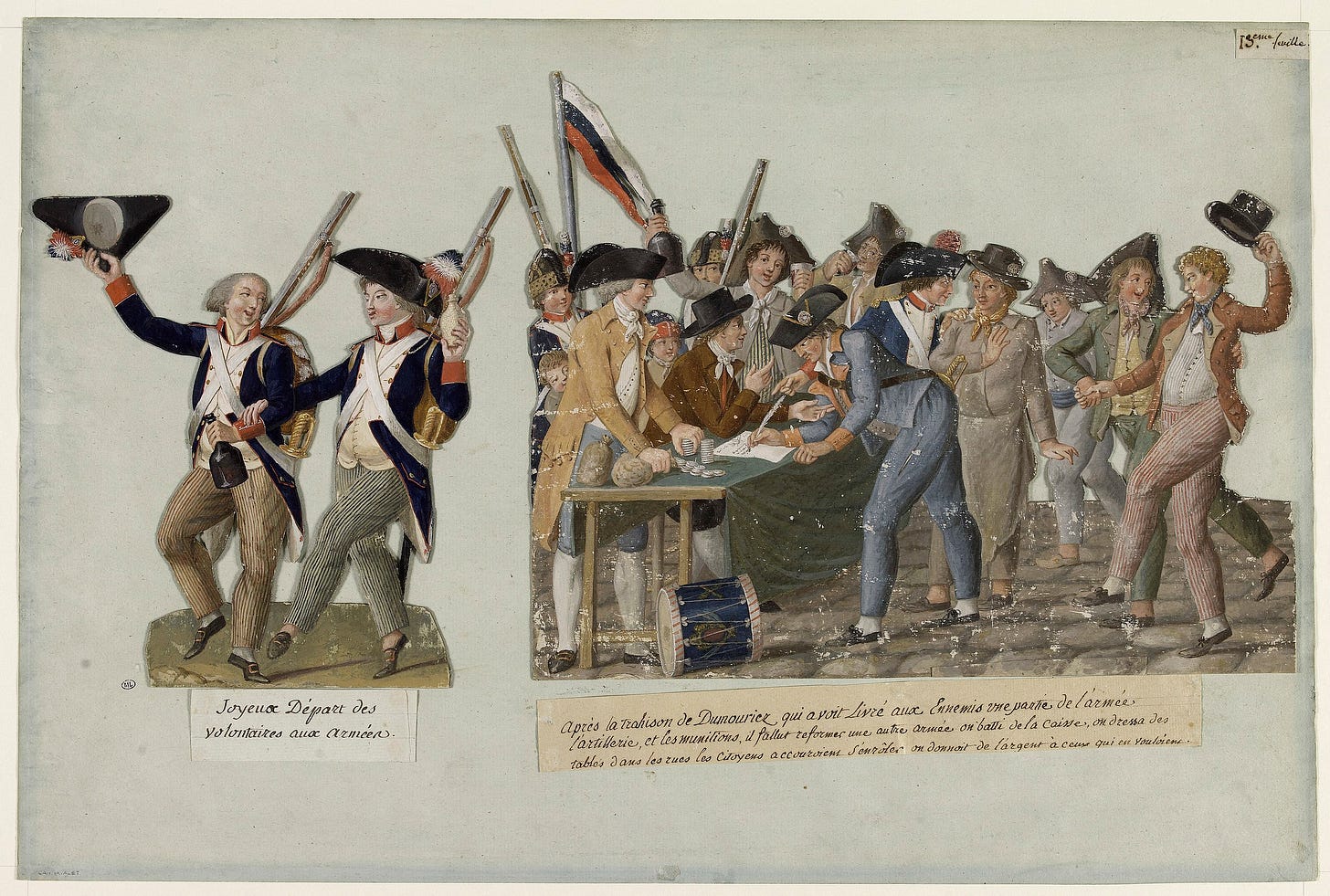

The case of the French army illustrates this revolutionary dynamic in its most familiar form. The impact of revolutionary disruption was an immediate and profound leap forward in modern war—one that would have been impossible without a willingness to question and break the practices of the ancien régime. Although the sum of the changes is too vast to catalogue, three paradigm shifts stand out in particular:

1. Mass mobilization

Through the introduction of conscription, France was able to raise enormous citizen-soldier armies to replenish its losses. (The 1793 levée en masse alone called for 300,000 men, at a time when Britain’s entire standing army consisted of 70,000 men.) Conscription, rarely used in Europe before 1793,2 became a kind of demographic super weapon, allowing France to leverage its entire population and transforming the nature of war from a contest of royal armies into a struggle between nation states.3

2. Centrally directed war economy

In lieu of the patchwork of guilds, contractors, and private aristocratic enterprises that made up the pre-revolution European supply chain, France adopted a command economy optimized for war: foundries, powder mills, and workshops were reorganized or nationalized; calibers and components were standardized; and production was coordinated by engineers and state inspectors. To contemporaries, the scale of state intervention was astonishing; such state interference would have been unthinkable for the opposing Coalition leadership.

3. Extreme meritocracy and individual agency

Dissolving the aristocratic monopolies that had dominated the officer corps resulted in a promotion system codified in competence and battlefield performance. Davout, Soult, and ultimately Napoleon had the opportunity to rise quickly through the ranks as talented commanders who would have otherwise remained invisible under the ancien régime. Meanwhile, radical innovations to the basic underlying structure of field armies, like the flexible corps system, created an environment where individual initiative could flourish, producing a more adaptable and aggressive leadership culture. A glimpse of this came at Marengo in Northern Italy, where General Desaix, acting entirely on his own initiative, intervened at a critical moment and salvaged a battle Napoleon was on the verge of losing.4 Such autonomy reflected a system that encouraged and rewarded independent action. This willingness to question the traditional link between nobility and command from first principles marked a profound break from centuries of inherited authority.

It is no surprise, then, that France commanded the continent for almost two decades. Britain, despite its army’s professionalism, needed years to adapt and ultimately relied on a continental alliance to restrict French power on land. What began as a marginal edge had compounded via factors that contributed to nonlinear growth into regularized superiority.

I think a loose computing analogy is quite apt, as a revolution in institutional design is similar to a revolution in computer architecture: a change in the underlying system architecture affects the performance of everything built on top.

Conscription expanded the state’s computational “cores,” giving France far greater raw processing capacity; the corps system introduced military “multithreading,” enabling independent units to maneuver and act in parallel; and meritocratic promotion elevated the quality of strategic decision-making itself, producing more advanced “processors” in leadership.

In other words, it’s difficult to beat a M4 as a Pentium 4, no matter how many of the latter you might have.5

The Navy

Less well remembered is what happened to the French navy. Given the near-parity between the fleets before 1789, it is certainly striking that after Trafalgar in 1805, the French fleet ceased attempting major fleet actions and was reduced to harassing British commerce. This naval collapse certainly appears puzzling in light of the transformation of her land forces, but I argue it arose from similar forces but was applied in a domain where they were fundamentally misaligned with the underlying system.

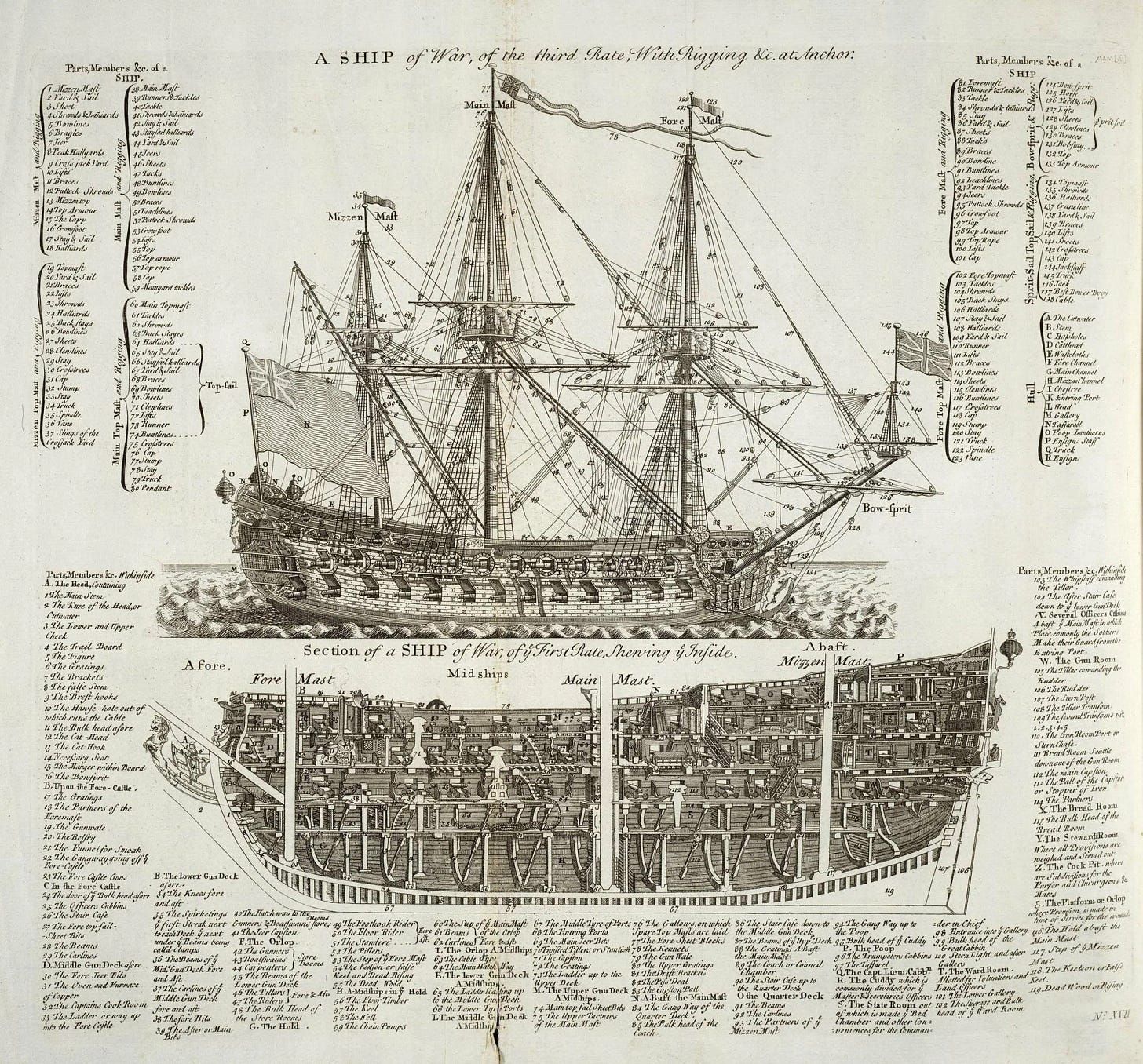

1. Long-horizon, capital-intensive bets.

While the army could scale almost instantly and outpace competitors through conscription, the navy was shackled to much longer cycles. A ship of the line took years to design, lay down, and fit out; its masts depended on timber planted decades earlier. (The Danes were still harvesting naval forests in the 2000s from trees planted in the early 1800s.) You can pivot your manpower policy via decree, but you cannot pivot your fleet without rewriting decisions made a generation earlier. This deep infrastructure (e.g., dockyard capacity, timber reserves, spread-out supply chains) to build technical marvels of the time is perhaps analogous to the painstaking investment process in today’s semiconductor fabrication. Naval production can’t be easily refactored and parallelized the same way that training a battalion could be via manual rewrites and a season of training. The very domain where the army gained an edge from speed was one where speed was simply not available.

2. Reconstructing a Working System.

The Revolution’s command economy revitalized the army because it replaced a genuinely archaic, decentralized patchwork. The navy was different. Long before 1789, French officials had understood that fleets required oversight of the aforementioned “deep infrastructure” under a single ministry. The tumult of the Revolution disrupted this working engine, which, through generations of trial and error, had produced the material and manpower flows required to maintain a peer to Britain and achieve the stability required for long naval campaigns. Committees sought changes where changes were not needed; thus, in seeking a vector of innovation, revolutionary France stumbled across vectors of useless disruption. This is not to say the French Navy did not need reform. It did, especially to keep up with rivals such as the Royal Navy, which was certainly innovating steadily. But the needed improvement was gradual; you cannot uproot an institution and expect it to thrive.

3. Tacit Knowledge

Like any complex human system, “operational effectiveness” relied on what economists today would call organizational capital: the stock of tacit, often unwritten, collectively held know-how embedded in the decades of experience of crews, petty officers, and long-serving captains.6 Particularly, these skills, like seamanship, gunnery drill, formation-keeping, and damage control, were not procedures that could be reconstructed from first principles, but rather knowledge only gained through the experience of repetition, complex relationships of apprenticeship, and time at sea, culminating into a form of group competency.

A single broadside naval gun of the early 19th century required a dozen or more men operating in perfect coordination; a fleet required dozens of such ships to maneuver in formation, fire for effect, and repair damage under sail, in weather, and often in smoke-filled naval battles. This knowledge was cumulative and fragile and needed to be passed down from the previous generation to the next; the revolutionary purges liquidated such knowledge as officers, being members of the aristocracy, fled or were executed. Mentorship chains snapped, training cycles were ignored, and ultimately, tacit knowledge was lost.

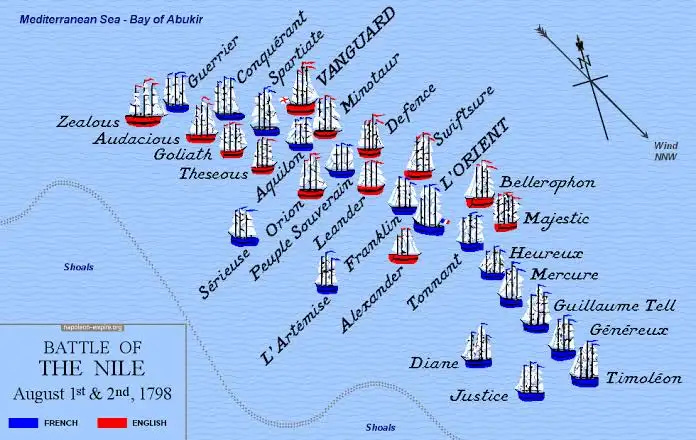

The effect was visible in battle. At the pivotal Battle of the Nile, which doomed Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign, Nelson’s initiative and command experience were amplified by deeper structural advantages: British crews fired roughly two to three times as fast as their French counterparts; the loss of experienced French petty officers destabilized damage-control efforts once ships were engaged; and degraded seamanship and local verification left supposedly impassable shoals navigable, allowing the British to outmaneuver and double the French line. It was a clear demonstration of how revolutionary disruption destroyed tacit competence at every level simultaneously.

Perhaps a relevant modern analogy is a veteran SRE team maintaining a sprawling microservices architecture. No single document explains why the system works, and its reliability depends on engineers who understand its quirks, failure modes, and unwritten rules. Remove that team abruptly, and the system becomes brittle. The French Navy suffered the same fate, overfixating on hyperrational reconstruction.

Thus, in the complex domains of naval organization, management, and execution, Burke’s belief in the latent wisdom contained in inherited practices of past generations had been broadly correct: a navy is a complex machine that suffers when expectations of performance and reconstruction temporally coincide.

III. Systems Thinking

WE CANNOT CHANGE THE HUMAN CONDITION, BUT WE CAN CHANGE THE CONDITIONS UNDER WHICH HUMANS WORK (James Reason, 2000)

The experiences of the French Army and Navy illustrate two aspects of a single revolutionary movement. On land, breaking inherited structures unlocked dormant potential, but at sea, the tradeoff made less sense, as breaking them destroyed the accumulated organizational capital that made the system function.

What matters for applying these lessons beyond history is systems-level thinking. There is a persistent temptation to entirely ascribe outcomes through individuals; that is, to tell great-man stories of history. But Nelson was not produced in a vacuum. He was shaped by decades at sea, by critical mentorship under Jervis, by repeated opportunities to succeed and fail, and by crews whose collective competence, morale, and respect amplified his talent. Likewise, Napoleon, however brilliant, could not conjure the tacit knowledge liquidated by purges, nor could he plant the trees required to build a fleet twenty years earlier. Systems contribute to the development of individuals and their success just as much as individuals influence and reshape those systems.

I think this distinction is helpful when considering why radical change succeeds in one domain but fails in another. The French army of 1789 resembled a greenfield startup; knowledge in a new domain is limited, so growth outweighs potential loss. Rapid change has compounding effects and is arguably required to innovate when the status quo is defeat, as was the case in the disorganized masses post revolution. The navy, on the other hand, resembled a large-scale engineering organization where the opposite was true; in a thoroughly explored domain, its reliability depended on accumulated expertise, stable interfaces, and deeply embedded tacit knowledge. Purge that knowledge, and the system collapses, not from lack of effort or courage from those who constitute the system, but from systemic changes which lead to a loss of collective competence.

History also offers a word of caution in ascribing finality to these patterns. These were not immutable traits of France or Britain, but situational responses to specific pressures confined within a specific period of history. The French navy eventually stabilized into a more iterative mode of development, producing the first purpose-built steam battleship in 1850, ironically named Napoléon. Britain, in turn, discovered through the Boer War during the turn of the 20th century that its incremental methods of warfare had grown obsolete in the face of a new foe, forcing radical changes in doctrine, organization, and equipment. An optimal approach in one era may require revision in another.

The reader might question the excessive focus on a historical episode as a case study. I think it’s because state conflict offers an unusually clear stress test in institutional design. Unfortunately, war represents perhaps the harshest collision between ideals and reality. With a clear opponent to index against, it exposes failure quickly and exacts payment in blood, emanating strongly within our consciousness.

Ultimately, the decision between incrementalism and revolution is not moral but situational; neither approach is universally superior; each solves a different class of problem appropriate for a specific challenge. The real challenge, for states, navies, and startups alike, is knowing when to apply which. Founders arguably face the same dilemma as reformers; it’s often not immediately clear which parts of the past are inefficiencies and which are critical scaffolding. Iteration on poor foundations results in stagnation and defeat to incumbents. But blow up the wrong things and you lose the required industry tacit knowledge. The mode of change matters, and so does the timing.

Blenheim’s legacy remains curiously visible in Britain. The battle endures in regimental symbolism through formal battle honors, selectively embroidered on regimental colors, and in Blenheim Palace, constructed to commemorate Marlborough’s victory and later the birthplace of Winston Churchill. The battle signaled Britain’s emergence as a consequential continental power following its tumultuous seventeenth century of civil war, regicide, and revolution.

A notable early exception was Sweden’s indelningsverket (allotment system), developed in the seventeenth century and refined under Gustavus Adolphus. It functioned as an early form of systematic mobilization, enabling resource-poor and sparsely populated Sweden to field disciplined, scalable forces during the Thirty Years’ War. I highlight this case because I think it illustrates how nation-defining transformative change can arise through sustained, unusually effective leadership by a series of individual leaders over decades rather than through a mass political revolution.

There’s an argument that revolutionary conscription marked a formative moment in modern European nationalism. By mobilizing a significant portion of the population for a shared military purpose, the levée en masse encouraged individuals to think of themselves as French citizens acting on behalf of the nation, rather than as residents of particular provinces or departments.

A quote attributed to Desaix upon arriving at Marengo, and a personal favorite: “This battle is completely lost. But there is time to win another.”

This is a somewhat ironic comparison, since processor architecture advances largely through Burkean, incremental refinement. But I believe the subject of the analogy, human organization and incentivization, to be far more pliable than silicon.

Reed Hastings once remarked that “culture is our product,” a formulation that captures how organizational culture functions less as an outcome and more as a critical governing variable. In complex systems, culture at any given moment acts as the derivative of tacit knowledge, determining whether that knowledge is accumulated, transmitted, and refined over time or instead dissipates through turnover, disruption, or misaligned incentives.

An amazing read! Lot of work and effort put into this piece.

It took me a few revisits to finish, but it was worth it since I believe I got a bunch out of it